“With colors, it’s like they wrote their lives.”

We all tell our stories in different ways.

Through the words we write, the photos we take, and the conversations we have, we share a piece of ourselves with the people around us.

We consider something a work of art when it connects with others in a special way.

A book that captures an era.

A song that creates an atmosphere.

A painting that evokes emotion.

But what happens when the form of expression is different from what we’re used to?

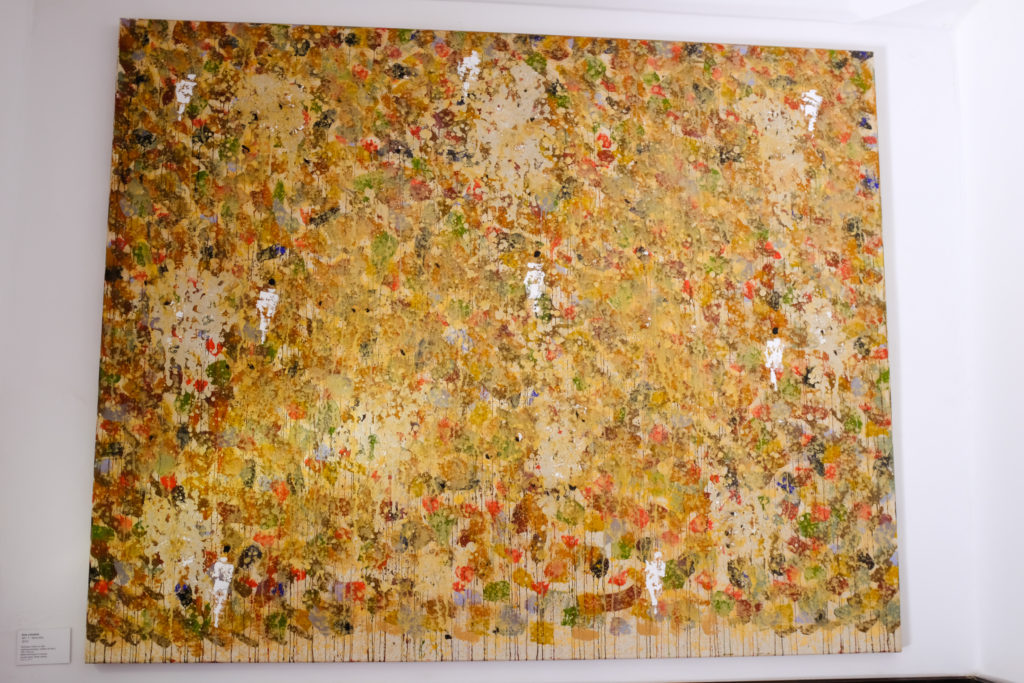

We’re familiar with Pollock-like paintings like the one on the left, and recognize it as abstract expressionist art. In contrast, we wouldn’t see rugs like the one on the right in the same way.

They’re visually similar. So why the difference in perception?

I wasn’t sure how to reconcile this when I visited Musée Boucharouite, a museum about Berber rugs called boucharouites.

Patrick, the founder of the museum, challenged our notions of art and self-expression.

These rugs, he explained, were made decades ago by elderly Berber women in small villages around Morocco. They didn’t have access to things like electricity or inspiration from the outside world, and they never considered themselves as artists.

Still, they felt compelled to create beauty, and although the rugs were created for practical reasons, they were also a medium to express what had happened in the women’s lives. They illustrated concepts like birth and death or expressed their feelings toward nature.

Patrick pointed out a rug that had drawn many to comment on how it looked like an Impressionist painting.

The rug was crafted in such a way to depict a scene of spring — the white of snow melting, a bluish stream gurgling nearby, green grass starting to peek out underneath the ice, colorful flowers appearing here and there.

“It’s like a Monet!” Patrick exclaimed.

As we walked around the museum, Patrick talked about the stories that each rug told. It felt like the rugs began to open themselves up to us, layer by layer.

Part of what makes them so interesting, I learned, is how their materials add special significance.

Boucharouites are made from used clothing, often from family members. This makes them intensely personal, as they are literally created from bits and pieces of the people who matter most to the artist.

One rug was made from the dresses of a woman’s daughters over the years. It was her homage to them, a visual timeline of how the girls grew up.

So many details that I had paid almost no attention to were revealed like little surprises.

I’d seen this piece, and appreciated the colors and textures of it.

Apparently, it reminded viewers of a variety of different things — a lion’s mane or fireworks, for instance.

I didn’t know that the squares at the top represented agricultural fields, or that the flowiness of the rest of the rug was like wind blowing through a meadow.

“You’re supposed to smell the flowers, feel the wind on your face,” said Patrick.

I definitely didn’t know that the artist intentionally used a specific color to evoke images of birds flying through.

But after you see it, you don’t unsee it.

Boucharouites told the unique stories of the women who created them, and Patrick explained how powerful they could be for people who connected to them.

One rug had a pattern repeated over and over: concentric diamonds, with a dot in the center. Then at the bottom, the pattern abruptly changes, with a very noticeable area filled in with black.

It seemed to have some specific message behind it, but I couldn’t understand what it was.

Then, Patrick explained that diamonds are a symbol of fertility, and the dot at the center represents a child. This was a rug about motherhood.

Looking closely, you can see that the woman who made it attached the bottom section to the original rug.

In this part of the rug, there are two dots within the diamonds. Yes — she had twins.

And then, there is the black. The color black signifies problems, or difficulties. The area on the left is filled with black, along with two lines that open up to the two dots in the center, which symbolize her legs opening up to her children.

With this, the woman is telling us how she struggled with the birth of her twins. It’s her story of her own experience with motherhood.

We heard from Patrick that two women who were twins, after learning about the meaning behind this rug, took a photo with it and sent it to their mom and told her that they loved and appreciated her. They were young adults who had never thought about what it was like for her to have twins.

And so, we kept diving into the incredible stories behind these rugs.

Through these rugs, women told tales of hope, loss, and acceptance.

One of my favorites was a piece that surprised me with how thoughtful it was.

It was a story told in three parts. In the first part, the woman, represented by red, meets and falls in love with a man, represented by yellow.

Then, there is the second section. There is a lot of joy and love (blue) but there are also many other things happening, including problems (black).

At the center of this, however, were their two kids — the two lines that stand out in the middle. They were the light of their lives.

In the last section of the rug, the lines represent the people in their town, and their two kids are becoming new members of the community. The lines extend and then end with a teal color, which symbolizes happiness and paradise.

We wandered around for hours, looking and re-looking, hoping to see more each time than the time before.

Going back to the boucharouite made from the dresses of the artist’s daughters, we pause and focus on a small tuft of fabric, vibrant in color but easily unnoticed.

It is bold and free — a wish from a mother to her daughters, a way of saying, “This is for you.”

These rugs: they are the archives of the women who made them.